IV: Recognizing the Challenges Confronting Investment Committees

From Balanced Managers to Specialist Managers

Investment committees face more increasingly complex challenges today than they did even a generation ago. Thirty years ago, for example, many institutional investors employed one or two balanced managers, which were often bank trust departments. The investment committee established an appropriate target asset allocation, such as 60% stocks (usually U.S. large cap) and 40% bonds (usually U.S. investment grade) and an appropriate range (e.g., + 10 percentage points) around these targets.

The balanced managers were hired by the investment committee and given the responsibility of selecting the individual stocks and bonds. Although the investment committee established a target asset allocation, the balanced manager often had leeway to adjust the allocation within the stated ranges based on their views of the markets.

By the 1990s, institutional investors had diversified their portfolios, with most abandoning balanced managers and hiring specialist managers, such as large cap equity, small cap equity, international equity, and fixed income. In portfolios today, we see several additional mandates, such as emerging markets, real estate, high yield, private equity, and various hedge fund strategies. The specialist managers usually have little knowledge of the overall portfolio and simply focus on their particular mandate.

Institutions Without Investment Staff

Consequently, for institutions with no investment staff, the investment committee is responsible for establishing investment policies, including the target (i.e., strategic) allocation, employing any deviations (i.e., tactical allocation) from the target, as well as the selection and termination of the investment managers.

In this model, investment consultants usually are hired to assist in the process, but the investment committee has ultimate responsibility for hiring and firing managers. For portfolios large enough to hold separate accounts, investment committees often will conduct manager searches, interviewing the candidates before selecting the most appropriate manager for each particular mandate. Once the managers are hired, investment committees may perform their own additional due diligence by meeting periodically with the managers.

For smaller mandates where mutual funds and other commingled funds are the preferred vehicles, investment committees will typically rely on the investment consultant to provide information on the managers. Ongoing due diligence may be provided by the investment consultant, but past performance is frequently a key factor in this process.

Furthermore, the investment committee is responsible for asset allocation and determining any deviations from the targets. These deviations could be intentional, overweighting (underweighting) of asset classes based on market views, or unintentional, simply due to a lack of rebalancing back to targets after market movements. In either case, the investment committee is responsible for reviewing the actual asset allocation versus the target allocation.

The increased complexity of institutional portfolios over the last few decades has changed how investment committees approach their roles. But is this the best governance structure for managing institutional portfolios? Should investment committees be responsible for selecting managers and allocating assets?

Barriers to Excellence

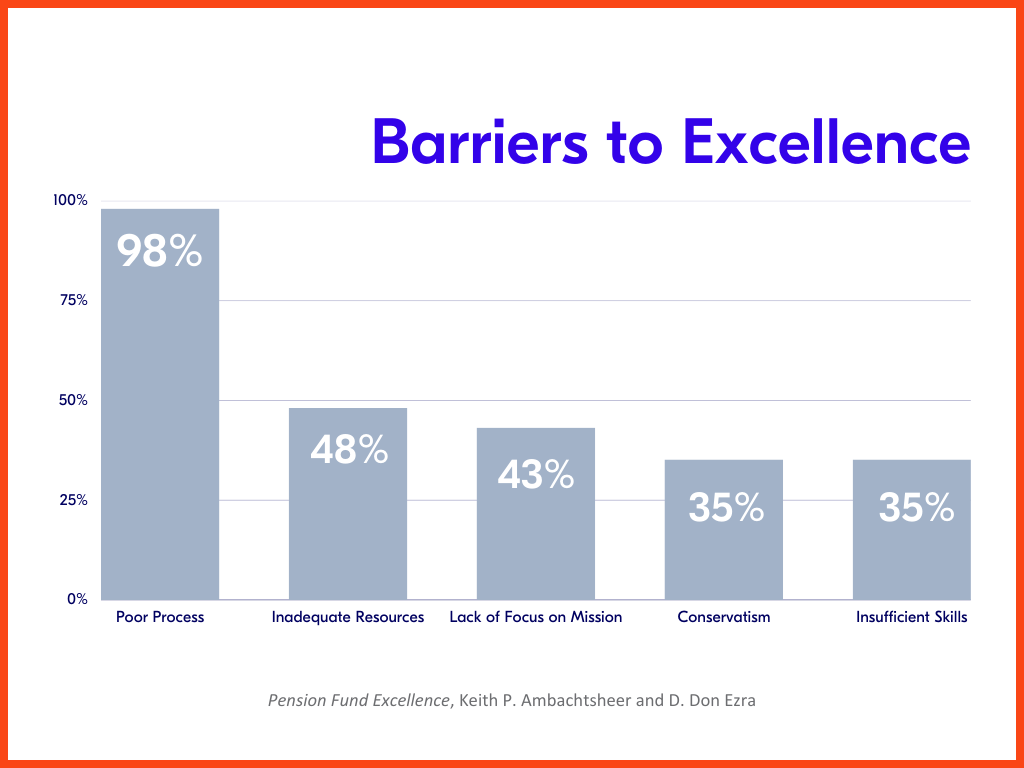

In their book Pension Fund Excellence, Keith Ambachtsheer and Don Ezra identified barriers to excellence for pension funds. In a survey of 50 senior pension executives, 98% cited poor process (decision structure, communication, and inertia) as a major hurdle to achieving investment goals. Other factors cited were inadequate resources (cited by 48%), lack of focus on mission (43%), conservatism (35%), and insufficient skills (35%).

Although focused on pension funds, the survey’s findings apply to other institutional investors. Many pension plan committees are staffed by employees who spend only a few days a year on investments, as they have other full-time responsibilities. This is not unlike endowment/foundation committee members, who are volunteers, typically meeting four times a year.

Committee Structure and Process

Consider the typical investment committee. Do the members possess sufficient investment knowledge and skills? Do the structure and processes provide adequate resources for informed decisions?

Investment committees are often comprised of five to ten individuals with varying degrees of investment knowledge, who meet quarterly, seek consensus, and base their decisions on comfort. By meeting quarterly, committees may miss opportunities to act on investment opportunities, or on the other hand, believe they must act when action is not warranted.

Because the committee members either work together (pension plans) or are volunteers (endowments and foundations), they are usually collegial and avoid confrontations. Rarely are decisions reached in a contentious 5-4 vote. In fact, 8-1 votes are also unusual, as a consensus is usually reached before acting. With varying degrees of investment knowledge, a large group, and a desire to become comfortable with an investment strategy before proceeding, investment committees rarely are contrarian or invest in strategies before others.

By investing with the “herd,” committees seek to limit reputation risk. To achieve superior returns (if that is a goal), however, an investment committee must be willing to invest differently than its peers. Once an investment strategy has become “mainstream,” the exceptional returns have been realized.

In many cases the major hurdle to achieving superior performance is the committee structure, which leads to implementation shortfall. Implementation shortfall includes delays in decisions due to lack of information, insufficient knowledge, failure to reach a consensus, inability to schedule a meeting, and lack of accountability (no one is solely accountable for performance).

Additionally, with the proliferation of managers and new investment strategies, investment committees have been unable to spend sufficient time interviewing and performing ongoing due diligence on the managers. Thus, they have had to rely more on staff, consultants, or fund of funds managers to perform this due diligence.

Today’s fiduciaries oversee portfolios more complex than ever before. What may have worked years ago, may not work as well today. In the next post we will review how boards and investment committees can improve the governance structure to avoid implementation shortfalls and remove any barriers to excellence.